Sixty-eight-year-old African American grandfather Eurie Stamps was lying on his stomach in his own kitchen, his hands above his head, when Officer Paul Duncan shot him dead.

The M-4 rifle that Officer Duncan used to kill Eurie Stamps

Officer Duncan says it was an accident. But Stamps's family says that when Duncan killed the elderly grandfather, his finger was on the hair-trigger of an assault rifle, pointed directly at Mr. Stamps, with the safety off. Any slight movement, even a flinch, would have prompted Duncan to fire. And that’s exactly what happened.

That was in 2011, during a SWAT raid on Mr. Stamps’ home. The Framingham, Massachusetts SWAT team was looking for Mr. Stamps' stepson, whom they suspected of selling drugs. Like special forces commandos in search of Osama bin Laden, the overly militarized police broke down Mr. Stamps’ door early in the morning, threw a bomb into the home to disorient its inhabitants, and stormed inside.

Mr. Stamps immediately complied with the officers’ orders. He lay on his stomach and put his hands up. At no point did he resist. At the time of the raid, the officers knew Mr. Stamps lived there and would likely be home when they barged in. The police didn’t consider him a threat. Nonetheless, after the SWAT officers had established complete control over the situation, Officer Duncan stood over Mr. Stamps with his finger on the trigger of an M-4 rifle (pictured), which he pointed directly at Mr. Stamps.

Duncan’s finger pulled the trigger inadvertently. But the series of actions the officer took before this accident were reckless and unreasonable, and violated Mr. Stamps’ Fourth Amendment rights, as did the accidental shooting that killed him.

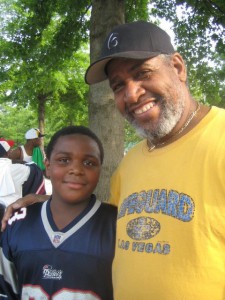

Eurie Stamps and his grandson Christian

Mr. Stamps’ surviving family is suing Officer Duncan under section 1983 of Title 42 of the US Code, the federal statute that grants Americans the right to sue police officers and departments for civil rights violations. Officer Duncan’s defense in the lawsuit is absolutely shocking, and if accepted by the court, would produce disastrous results—particularly for Black and Brown people most often targeted by aggressive police action.

Established Fourth Amendment law in the First Circuit, which sets federal law for Massachusetts and several other states, says it is unconstitutional for an officer to point a loaded weapon at a compliant, non-threatening person. Doing so qualifies as unreasonable police action and violates the law. But in the Stamps suit, Officer Duncan argues that, because the final act in the chain of events that led to his killing of Stamps—pulling the trigger—was an accident, he cannot be held liable for the killing.

Duncan invokes the qualified immunity doctrine, which holds that police officers cannot be sued for conduct that doesn’t clearly violate the law, conduct which at the time appeared reasonable.

By that theory, while the actions that preceded the shooting—taking the gun off safety, pointing it at Mr. Stamps—were clearly unconstitutional, as soon as Duncan (accidentally) pulled the trigger, he became immune from liability for his conduct.

As my colleagues write in a friend-of-the-court brief, the defendant’s argument is dangerous and bizarre. It would, if accepted, produce a legal doctrine that provides incentive for police officers to injure or kill people they have subjected to unconstitutional police practices.

It inoculates officers if, but only if, their unreasonable actions cause injury. As applied to the facts of this case, this rule means that an officer who unreasonably aims a firearm at a civilian’s head would incur § 1983 liability if the civilian is not shot, but not if the firearm discharges and the civilian is killed. Other possibilities abound. For example, if an officer seeks to extract a confession by dangling a suspect over the ledge of a high-rise, the officer will be liable under § 1983 if he later pulls the suspect back to safety. Yet, under the defendants’ rule, the officer will acquire immunity if his grip should fail and he accidentally—but as a consequence of his prior, intentional, and unreasonable conduct—drops the suspect to this death. [Citation removed.]

Eurie Stamps, second from left, celebrates his birthday with his four children (left to right) Kyon, Marlon, Robin and Eurie, Jr.

A ruling accepting this argument would be terrible and absurd under any circumstances, but particularly given the climate of militarized policing in the United States today—a burden borne disproportionately by Americans with darker skin. Across the nation, police departments armed with military weapons and flash-bang “grenade” bombs barge into people’s homes in the early morning, simply to serve search warrants or arrest suspects. More often than not, these raids are conducted to look for drugs or someone suspected of selling them. An ACLU survey of departments throughout the nation found that 71% of the targets of these militarized raids are people of color.

Moreover, as my colleagues argue in their brief, Black and Latino people are subjected to more police stops than whites, even when controlling for crime and other factors. Studies show that “race can [] influence the probability that the police will erroneously harm an innocent person during an encounter.” Other studies “have extensively documented unconscious negative associations about people of color, including an association between Blacks and crime.” Americans are more likely to think Black people holding innocuous objects are holding guns, and to erroneously “shoot” those Black people when given the opportunity. Subjected to more dangerous SWAT raids and police stops, and the targets of racist tropes about criminality and Blackness, people with darker skin are much more likely than whites to suffer the repercussions of unconstitutional policing.

Therefore, a legal doctrine establishing that officers cannot be held liable for the final, accidental twitch in a string of unconstitutional actions would further endanger individuals and communities already bearing the brunt of disparate, aggressive policing. It’s our hope that the First Circuit will clearly rebuke the defense’s dangerous argument, sending an unmistakable message to police officers throughout the northeast: you will be held liable for your mistakes when the likelihood of making them is compounded by prior illegal actions. You cannot turn the safety off your gun and then illegally point it at someone, only to claim that the final act of shooting them was accidental and so absolves your prior conduct.

Stay Informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.