By Rahsaan Hall, Director of the Racial Justice Program at the ACLU of Massachusetts

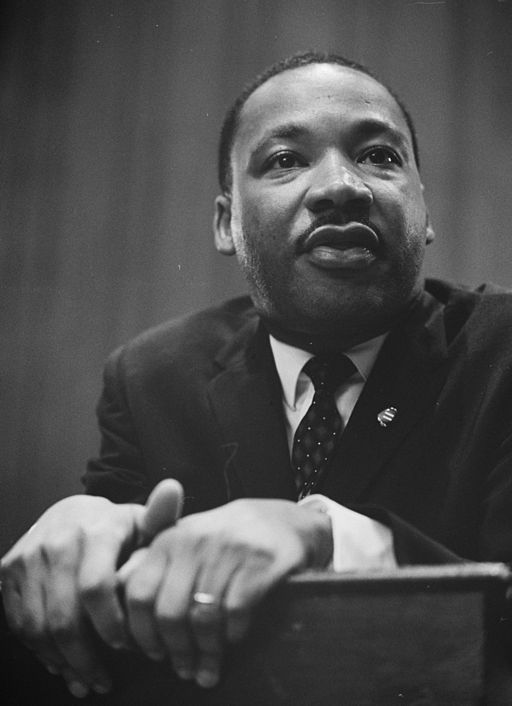

This year marks the 91st anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s birth. We observe the occasion, as we always have, with equal parts celebration and solemnity, joyous rest and purposeful work—our shoulders to the wheel but our eyes on the horizon. Perhaps more than any other American, King prompted us to think, in profoundly human terms, of the passage of time—the distances between then and now, today and tomorrow—not as a dead procession of deterministic events, but a soulful, intentional march toward freedom.

MLK Day is an opportunity to reflect on King’s memory, but also his futurity. King understood that the past is neither dead nor even past, and so we honor his legacy by nurturing it, and letting it nourish us in turn for the work we have yet to do. For this reason, it’s customary on MLK Day to take stock, and to assess whether we have gotten any closer to realizing King’s prophecy of a promised land, whether we have loosened or even cast off the chains of hatred, repression, and inequity. Sadly, as is all too often the case, we find our institutions lacking, and our most naïve notions of steady, universal progress—sanitized versions of King’s radical manifesto—to be fantasies. In only the third week of 2020, we must admit that our new decade has had an inauspicious start.

We have stood, once again, on the precipice of war—a danger that troubled King profoundly in his lifetime. In the years before he was murdered, King spoke frequently about the brutal intersections of racism, violence, and militaristic capitalism. He reminded us, for example, that when faced with the overwhelming and appalling spectacle of war, we must not forget its appurtenant maladies of greed and repression. Each of these evils, he concluded, entails and upholds the others: “[w]hen machines and computers, profit motives and property rights, are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered.” There is no doubt: these triplets are sounding a triumphal march.

Just as we witness the rise of one evil, another follows in its wake. We have seen the increase in hate crimes buttressed by the racist, xenophobic rhetoric and policies of the current presidential administration. At the same time, corporate interests have commodified our existence, shredding the social fabric and replacing it with an impersonal network of data points. As people become easier to quantify and measure, they are more easily controlled, targeted, repressed by both ruthless privateers and government agents alike. In an age of pervasive data surveillance, just as King predicted, the giant triplets lumber forward, their steps tumbling and compounding in a fearful crescendo.

King spoke out against militarism and was condemned for his stance on the war in Vietnam. When King was admonished to limit his concerns and advocacy to local affairs he responded, “[America] can never be saved so long as it destroys the deepest hopes of men the world over.” King and his contemporaries believed that if America was to be redeemed it would have to ensure that the descendants of slaves had to be freed from the shackles that kept them bound. Within that mission was a recognition that the overall health of the nation was not only tied to granting particular rights to Black Americans but addressing the disease of militarism. King’s non-violence platform thus evolved to include more than peace for Black people in America, but also rooting out the militaristic violence and rapacity that drove conflicts throughout the world. The same militarism allied with racism and extreme materialism would lead to US intervention throughout the world under the guise of defending democracy.

King’s critique of militarism at the time was focused on traditional military involvement in global conflicts. But as the lines between the military and civilian law-enforcement blurred it became more important to speak out. Although King’s concern over militarism focused on US intervention in world conflicts and wars, it is not a stretch to suggest that those same concerns around militarism extend to police militarism. King would surely recognize that warlike action abroad inevitably lays the groundwork for warlike action directed inward—the targeting of “threats both foreign and domestic.” In this way, the War on Drugs and the War on Terror have created amorphous, nondescript enemies in a battlefield near you. The initiation of these wars is rooted in fears that stem from racist and xenophobic ideas, and the execution of these wars have led to countless casualties in oppressed communities—regardless of national borders.

We should not think of militarism as only local law enforcement acquiring military grade materials, but also their acquiring of military strategies and intelligence structures. Beyond accumulating military material—i.e. weapons and vehicles—militarism has transformed the culture, organization and operation of local policing. The culture of policing has changed when local police fight wars against drugs and terror. The organization of policing has changed with the creation of SWAT teams and other tactical units with specialized training and weaponry. Finally, the operation of policing has changed with the use of military intelligence analysis methods being used to address issues of community disruption and crime.

Militarism within police departments is a threat to our civil rights. The strategies and tactics include crime data analysis and strategy councils where police use data sets collected from police interactions and crime statistics, using facial recognition technology, location tracking programs, and social media monitoring. If we are truly to be a free nation, we must be one that does not offload the decision-making responsibilities of addressing crime and disruption in society to algorithms. We must not submit to what seems like the impartial, impersonal, inevitable logic of trial-by-computer. We must have the fortitude to build our communities together, face to face, side by side.

The counterinsurgency strategies and tactics that our government deployed in global theatres of conflict should not be used in our communities—but they are. Local law enforcement disproportionately deploys these strategies in Black and Latinx communities as well as other oppressed communities. Shrouded in a lack of transparency, police intelligence units mine data and crime statistics to develop crime suppression strategies that have questionable value and often come at the expense of vulnerable people. For instance, the Boston Regional Intelligence Center maintains a “gang database” that has dubious selection criteria, lacks audits and has no observable measures of accountability. In a digital age where every aspect of our day-to-day lives is a data point to be curated for corporate marketers and government surveillance, it’s all the more important that we resist encroachments on our privacy and civil rights.

In “Beyond Vietnam,” the same speech where King critiqued the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism, he makes a bold demand for people to put themselves at risk for the sake of peace. We are facing very dark and perilous times and the threat of the potentially unconquerable giant triplets loom large. Now is the time for people of conviction and valor to stand in opposition, at whatever risk to themselves, to advance the causes of justice by resisting the spread of militarism with every fiber of our souls.

The machinery of repression is always evolving, always being upgraded. It may have received a few new coats of paint since the 1960s, but the core remains the same. Just as King worked to dismantle the machine before us, we must do everything we can to hinder its insidious functions today. We must call for an end to gang databases and other civilian intelligence gathering strategies that can be used to further oppress Black, Latinx, and poor people, immigrants and religious minorities. We must call for a moratorium on the unregulated use of governmental facial recognition technology and other remote surveillance technologies. And we must call for limits on risk assessment tools in the criminal legal system that have been shown to further exacerbate racial disparities under the guise of technological sophistry.

Even in death, King was not conquered. The brash militarism of the state is no match for the conviction of the soul. King’s vision of resistance and hope lives in us today, as a thing of everlasting potential. Justice, King teaches us, will not thrive on its own; it will prevail if only we have the will—and the courage—to work for it. When we’re united in resistance and hope we are the unconquerable ones.